Some time ago I was invited through my Springer editor to an event for the International Festival of Science, which takes place every year in Genova, Italy. The theme of the soiree was something entertaining about “scientists making mistakes”. The room was full for about 3/4, and I was rather surprised that a few hundred people would come and pay a ticket just to listen to me. My surprise faded away when I sat next to Nanni Bignami, the renowned astrophysicist and popular TV communicator. He had been taking selfies with dozens of enthusiastic kids before entering the hall: obviously (what a relief!) people were there just for him, not for me. Anyway, I had prepared a funny talk for the occasion, which I am going to recycle as today’s letter for you.

In 1587, a young scholar of high hopes named Galileo Galilei presented two lectures at the Florentine Academy about the structure, site and size of Dante’s Inferno. At age 24, Galileo had already published his first scientific works, but now he wanted to show that mathematical physics – that recently invented method of investigation – was not just an effective technique for calculations, but could make a contribution to the noblest cultural debates, thus acquiring an intellectual status comparable to that of classical humanities. The opportunity arrived when the Florentine academics prompted him, a scientist, to resolve a literary controversy regarding the interpretation of Dante’s first volume of the Divine Comedy. What had happened to stir such an unusual request?

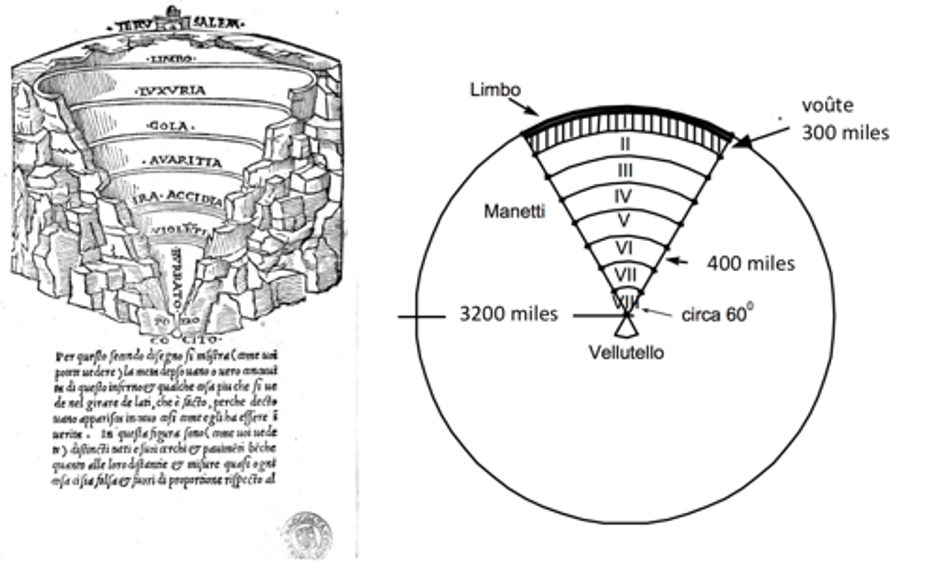

In 1506, a representation of the geography and geometry of Hell as described in the Divine Comedy had been published by the Florentine Antonio Manetti. Similar to pictorial representations already proposed by Giuliano da Sangallo and Botticelli, such models were deduced from Dante’s text through abstruse calculations, which, for the intellectual circles of the time, deserved to be carefully established. But in 1544 a certain Alessandro Velutello based in Lucca, a rival city of Florence, had published a severe criticism of Manetti’s work, proposing a radically different description of Hell. The two models were identical in terms of general appearance (derived from a careful reading of the Divine Comedy, see figure, left) but differed significantly in size. Velutello’s Inferno had linear dimensions about 10 times smaller than those of Manetti (figure, right). He assigned the same inverted-cone structure to Dante’s Hell, but with an overall depth of about 300 miles, instead of the 3,200 set by Manetti. The main objection to Manetti’s Hell concerned the structural stability of the “dome” that would have been necessary to cover such a large area (Dante’s Inferno is supposed to be situated below the Earth’s crust, right under our feet).

Galileo was called to settle the vexata quaestio and, as a Pisan living in and working for the Republic of Florence, he predictably deliberated in favour of the Florentine Manetti. He started with a confirmation of Manetti’s description: Hell is indeed a conical cavity whose vertex is at the center of the Earth, and whose axis at the level of the surface corresponds (obviously) with Jerusalem. The circle at its base has a diameter equal to the radius of the Earth, which is equivalent to say that, in a central section of the Earth passing through the axis of the cone, the sector covered by Hell occupies exactly one sixth of the area of the disk, corresponding to a volume approximately 1/14 of our planet (see again figure, right). To answer the central objections raised against the existence of the vault that covers the Hell, Galileo replied by observing that the ratio between the arch of a typical masonry dome (taking in comparison that of the Duomo, the main church of Florence) and its thickness is about 15, while for Manetti’s Inferno it is 3,200/400 ~ 8, therefore Inferno’s roofing had to be even more stable than that of the Duomo.

This architectural analogy had a profound cultural sense, given the importance that Brunelleschi’s perfectly rational design of the Duomo had for the men of the Renaissance. However, its scientific value is zero: if made to the size of Hell while retaining the same geometric proportions, the masonry of the vault would just collapse. In fact, materials science says that the resistance of the wall increases as the area of its section, but its weight increases as its volume. If all the dimensions are multiplied by the same scale factor, for example 10, the weight will be multiplied by 1,000, but the resistance only by 100; that is, it would be proportionally 10 times more fragile. It took Galileo almost forty years, with the famous scale drawing of the giant’s femoral bone whose thickness increases proportionally to the increase in size (appearing in his Discourses and mathematical demonstrations on two new Sciences) to acknowledge that he understood his error, derived from a purely geometric conception that does not take into account the physical laws of scaling.

But musings about the Physics of Hell certainly did not stop with Galileo. On the contrary, the subject has met with growing interest even in modern times. A hellish study was published by a certain John Howard in Applied Optics 11, A14 (1972), and applies the thermodynamics of radiation to conclude that Heaven must undoubtedly be hotter than Hell. (The author of this story allegedly should be the physicist Paul Darwin Foote, who published it anonymously in a 1920 bulletin of the Taylor Instrument Company; the version that appeared in Applied Optics was described as sent to the publisher by this John Howard, who claimed to have received it from William Koch, who had received it from Alan Bromley, who in turn had heard it from an unknown colleague… many decades before! Maybe He Himself it was…? some dark figure with horns, a pointy tail, and a hoof for the left foot…?)

Howard tells us that the temperature of Heaven can be calculated with good accuracy from a highly reliable source, the Bible, book of Isaiah, 30:26, where we read: Furthermore, the light of the Moon will be like the light of the Sun, and the light of the Sun will be seven times the light of seven days. From the fact that the light in Paradise must be at least 7×7 = 49 times that on Earth, it can be deduced (by the Stefan-Boltzmann law) a temperature of 793 K, or 520°C. A really uncomfortable temperature, for the lucky blessed heaveners. According to Howard, the exact temperature of Hell is a little more difficult to calculate, but from a passage in John’s Revelation 21: 8, we know that: The wicked and unbelievers […] will be destined for a lake that burns with fire and sulphur. Now, a “lake” of sulphur means that the temperature of the fluid must be at most equal to the boiling point, otherwise it would be a vapour and not a liquid. For sulphur this temperature is equal to 444.6°C, certainly uncomfortable for the unlucky damned, but already a little better than the 520 degrees to which the lucky blessed would be exposed. Therefore, Heaven is hotter than Hell.

A few years later, however, some mr. Tim Healey published in the Journal of Irreproducible Results 25, 17-18 (1979) an answer that combines biblical “evidence” with thermodynamics, to deduce that although Heaven is undoubtedly very hot, Hell is even hotter. The first value of 520 degrees for Heaven seems difficult to disprove even for mr. Healey. But for the Hell, Healey notes that Howard has wrongly assumed that the sulfur in Hell is at atmospheric pressure, like it would be on Earth. On the other hand, we do not have sufficient data to establish what pressure exists in the region of Hell. Then he figures that, if we were to compress all the damned souls to fit in the valley of Gehenna (a designated place of damnation, as recalled by several evangelical passages, e.g. Matthew 5.22 and 18.9, Mark 9.43, James 3.6), the pressure of Hell should rise to several million atmospheres. At such pressure, the boiling of the sulphur indicated in the Apocalypse must correspond, according to the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, to a temperature definitely much higher than 520ºC. Which proves that, although the temperature of Heaven is extremely high, that of Hell is … “damned” higher!

I will end today’s storytelling with one last anecdote that is regularly told as “a true story”, and when a story begins with “this is a true story” you can be pretty sure it is not. However, this is an interesting variant because, unlike the previous argument, it takes into account a variable volume of Hell, as needed to host all the incoming damned. In some websites this is described as the subject of a chemistry exam at the University of Washington; in other versions, the professor would be a Yale chemist-physicist; according to yet others, our hero has a very specific name, Dr. Schambaugh of the University of Oklahoma School of Chemical Engineering, and the subject was included in the final exam of May 1997. In fact, the story has been around since well before ’97, however it is nice enough to be told here

A physics professor proposes a written test for an exam to his students, containing only one question: “Is Hell endothermic or exothermic?”. Most students scrambled for mirrors, looking for some answer based on Boyle’s law, or the ideal gas equation of state. A student instead, the only one awarded at the end with the highest grade, wrote this answer: “First of all, we postulate that, if souls exist, they must have a certain mass. And we can ask ourselves, at what rate do souls enter and leave Hell? Many religions argue that all those who do not believe in their religion are unbelievers, and will end up in Hell. Since people usually belong to only one religion at a time, we can assume that virtually everyone will go to Hell, according to one or the other religion, including those who do not believe in any religion and are simultaneously disbelievers for all religions. Given the rate of World’s population increase, we can therefore deduce that the number of souls entering Hell is an increasing exponential. Now, let’s consider the rate of change of the volume of Hell that is necessary to accommodate all these damned souls. Boyle’s law says that to maintain constant pressure and temperature, the density must also be constant; now, if the volume of Hell increases at a rate lower than the entry rate of souls, the pressure and temperature of Hell will have to increase, until Hell erupts; conversely, if Hell increases in volume faster than the arrival rate of souls, the temperature will decrease until it freezes. However, I still cannot establish here with certainty whether the “Inferno system” is exothermic or endothermic. On a personal basis, I feel inclined in favour of the first hypothesis, given the following data: a girl that interests me very much has sworn that she will get in bed with me only when the Hell will cool down. Given the very low probability that this is going to happen, I am led to believe that the temperature of Hell is destined to increase.”